Here is a 2025 New Year’s resolution even you can make, and luckily, it has never been easier to keep. This year, take a vow to get more music into your life. “Life without music would be a mistake,” Nietzsche famously proclaimed, and we could not agree more.

Relaxing, motivating, immersive, life-affirming, these are just some of the many positive effects music can have on our mental and physical health, benefits that are well documented, and embraced by people all over the world.

Today, finding your favorite music has never been easier with streaming services like Apple Music, and Spotify offering instant access to millions of songs, all at the touch of a button. Today, recorded music is everywhere we go. Yet, not long ago, it almost did not exist.

“If you were looking to hear your favorite song, it wouldn’t be on the internet, or the radio, or even on a vinyl record, or cassette tape,” says Kevin Hall, electrical engineer, and Museum docent. “If you wanted to buy your favorite song, a recording you could take home, and play over and over whenever you liked, you’d be coming home with an 11-inch roll of perforated paper.”

Before radio, before the recording industry, the player piano, or “pianola,” was the only means of recorded musical entertainment. “This was a time when you might hear a concert once in your entire life,” says Charlie Bryan, Director of Operations. “And what would you hear? An opera singer? A choir? A marching band?”

The “piano roll” is an audio recording coded on a strip of perforated paper meant to fit inside an all-pneumatic, self-playing piano that automatically plays music—perhaps your favorite song—without musicians, and without electricity. No people, no wall outlets, no batteries, and yet, the player piano provides live music on command. Magical, mechanical, ghostly.

The concept of self-playing automated musical instrument existed as early as the ninth century. “People have always wanted machines that make music,” says Bryan. “We start that history with the music box, a device that inspired both the pianola, and Edison’s first cylinder phonograph.”

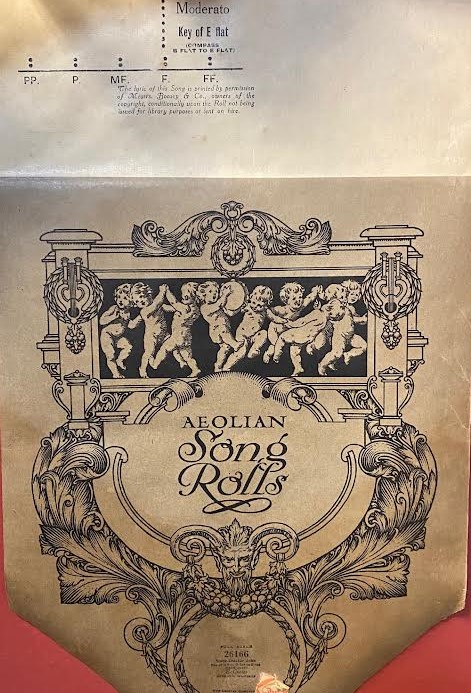

The first functional pneumatic player piano is credited to inventor Edwin Votey in 1895, and manufactured by the Aeolian Company in 1896. “It’s basically a mechanical box placed in front of a regular piano, and operates the keys using perforated rolls of paper,” says Hall. “In the beginning, pianolas operated without an electric motor, and relied on a purely mechanical and pneumatic system to operate.”

The pianola uses a roll of perforated paperto encode the music with patterns of holes, arranged much like the pins in a music box. Each hole corresponds to a specific note on the piano. Eighty-eight keys are connected to eighty-eight tiny holes on a metal tracking bar—which looks like a funny harmonica.

The master is recorded by a musician who plays a piano attached to a piano roll machine called a “puncher”, which records the notes using a system of punches to create the pattern of holes in the paper. Each horizontal line represents a specific time, and the spacing of the perforations indicate the note’s duration.

When the paper roll passes over the harmonica-like tracking bar, the perforation in the paper allows the air to flow through the corresponding hole, activating a pneumatic mechanism and triggering a hammer to strike the corresponding piano key.

A foot-operated pedals powers the set of bellows creating an air suction. This vacuum provides the energy needed to power the mechanism.

The player can even control the speed and dynamics of the performance by adjusting a speed lever or applying force on the foot pedals. This allows for expression, even though the notes themselves are pre-determined by the paper roll. After the roll has been played, the player can use the pedals to rewind it, preparing it for the next performance.

This ingenious design—using only air pressure and simple mechanics—made the pianola a true marvel of early automation.

In the early 1900s, companies such as the Franklin Piano Company refined and popularized the player piano, integrating the self-playing mechanism directly into the piano design. By 1910, all major piano manufacturers had at least one line of piano player. By 1925 pianolas were the most popular type of piano built in the United States, with thousands of songs selling millions of copies—unleashing an unprecedented variety of music including classical, ragtime, gospel, and the newest popular songs from tin pan alley.

In 1906, the Vocalstyle Music Company of Cincinnati, Ohio, introduced printed lyrics on their piano rolls, thus creating the world’s first karaoke machine. Now everyone—even you—can be the life of any party or social gathering.

Yet not everyone welcomed this new technology.

The most obvious were piano teachers, who thought it discouraged children from learning to play the piano. “Imagine, trying to compete with a professional recording that never hit a wrong note on the same piano your parents made you practice,” says Bryan. “It must have seemed like a complete waste of time.”

One way a live musician could compete, would be to incorporate nuance and dynamics into their performance. Player pianos, though musically accurate, sounded comparatively mechanical, with much less room for emotional expression. Plus, pianolas were still expensive, and required regular professional maintenance to keep the tunes flowing smoothly.

Sales of player piano rolls peaked in 1924, but declined in the mid-1920s due to improvements in electrical phonograph recordings. The popularity of player pianos continued to decline with the introduction of radio and the birth of the recording industry.

By 1929, and the devastating stock market crash, pianolas seemed to vanish overnight.

The SPARK Museum proudly displays an original 1928 Franklin pianola in their Radio Enters the Home gallery, where daily demonstrations are performed for visitors just like you—and yes, singing is encouraged. Stay grounded.