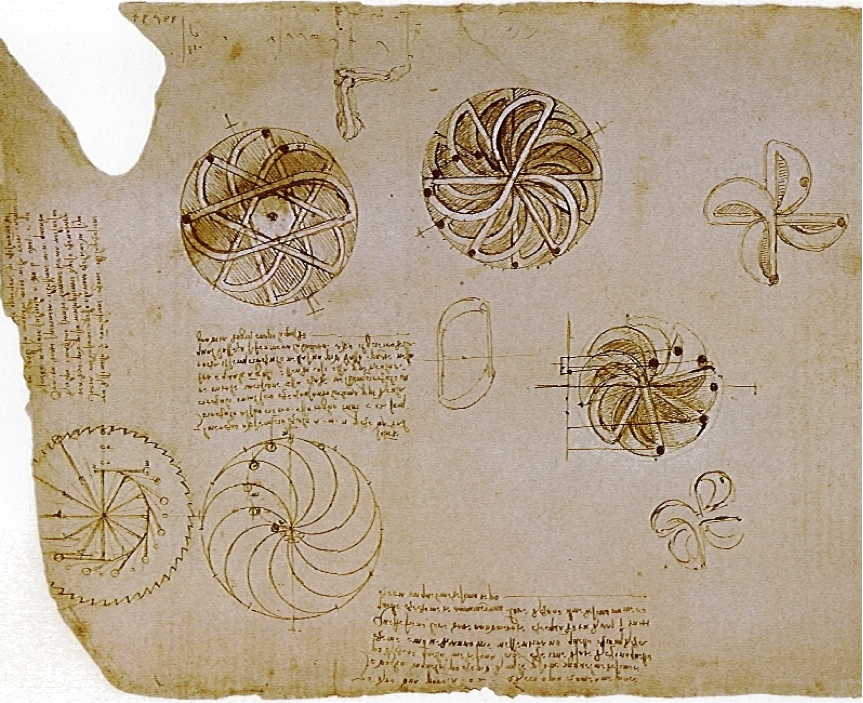

“Oh, ye seekers after perpetual motion, how many vain chimeras have you pursued? Go and take your place with the alchemists.” — Leonardo da Vinci, 1494

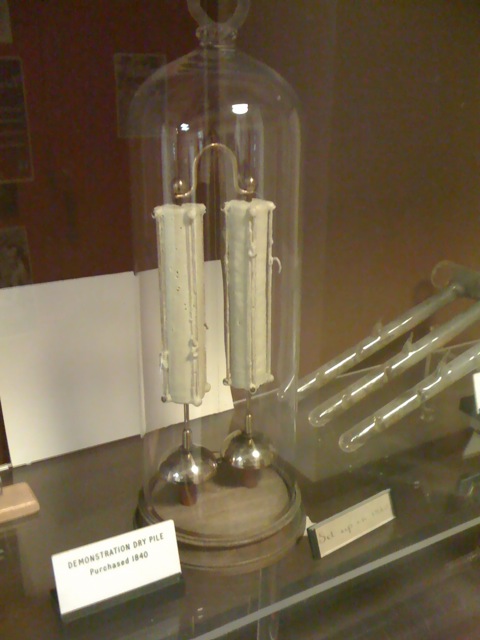

In a hallway inside the Clarendon Laboratory, at the University of Oxford, in England, there is a glass display case featuring an electric bell that has been ringing—completely on its own—for over 185 years. Since 1840, the Oxford Electric Bell, also known as the Clarendon Dry Pile, has been gently resonating, non-stop, making it what many consider the world’s oldest science experiment.

Generations of curious students and faculty have come and gone through those venerable hallways—and yet, class after class, year after year, that bell continues to softly chime. Might this marvelous, if annoying little device contain the secret to producing energy, and possibly run forever?

Such a discovery would be mind-boggling. No more fuel needed for your car, for your lights, for your anything. Such a discovery would transform life on our planet, offering 100% efficient, clean, endless energy—for everyone.

Images of El Dorado, the Fountain of Youth, cold fusion, and a free ham sandwich should all quickly come to mind.

The history of perpetual motion machines date back to the Middle Ages. One of the earliest was called Bhāskara’s Wheel, created by Indian mathematician Bhāskara II, and designed to produce enough energy to rotate itself, indefinitely.

It did not, nor did any of the other countless attempts at creating a device that could endlessly rejuvenate itself. Many talented, even brilliant, scientific minds, including Leonardo da Vinci and Robert Boyle, designed devices they hoped would run under their own power. Even the great mathematician, James Clerk Maxwell, explored the concept of violating the second law of thermodynamics in his famous thought experiment, “Maxwell’s Demon.”

Yet, eventually, for one reason or another, they all failed.

What all those curious inventors didn’t know was they were up against a cornerstone of classical thermodynamics—laws embedded in nature, too solid to even think of breaking.

“If your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics, I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.” — Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, 1927

In science, if something has never been known to fail, we call it a law. We can’t prove a law, but if something has never failed, we take it for granted it never will fail. These are the laws of nature, and the foundation our science stands upon. One of these laws is the conservation of energy, but it would be more accurate to say the preservation of energy.

It basically states, there is a certain quantity of energy in nature, no more and no less. That quantity does not change, no matter what form it takes. It cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed. The number always remains the same. Energy is always preserved. If you can’t find it, this law says to keep looking as the energy has to be somewhere. No exceptions to the laws of nature.

So how do we know, sadly, that the Oxford Bell is doomed to someday run out of power and stop ringing? Because of the second law of thermodynamics, and a concept so simple it can be hard for many of us to get our mind around: entropy.

Entropy is watching a drop of fresh cream swirl through a cup of black coffee, spreading into clouds, and then turning into mud. That’s energy radiating through friction, heat, movement, and even sound, which is all happening to the Oxford Bell.

The Oxford Bell was created by London instrument makers Watkin and Hill, and clearly inspired by 19th century, Italian physicist, Giuseppe Zamboni who developed a method of making early batteries by using very thin discs of tinfoil, glued to paper impregnated with zinc sulphate, and coated with manganese dioxide. This method allowed Zamboni to create a dry pile of over two thousand layers that stood like thick candle sticks approximately twelve inches tall.

They produced over 2,000 volts, and stored an electrostatic charge on their terminals for an extraordinarily long time. In other words, these are really powerful batteries.

Two outstanding examples of Zamboni machines are on permanent display in the Museum’s galleries. These rare instruments are composed of two dry piles that alternately attracted and repelled a pendulum situated between them. As with the Oxford Bell, it didn’t require a lot of power, and energy loss was minimal, contributing to its longevity.

Legend has it that the Zamboni devices on display at SPARK worked non-stop for well over a century. Zamboni may not have found the secret to perpetual motion, but he did successfully marry chemistry with mechanics, and create the world’s most efficient and durable battery. Even the Energizer bunny can’t touch that. Stay grounded.