“What good is a newborn babe?” is a favorite quote attributed to our beloved Benjamin Franklin, who, on August 27, 1783, was among a crowd of excited Parisians as they witnessed the first hot air balloon ascend majestically into the sky above the Champ de Mars.

Image Source: Blue Lion Guides

The story goes that while gazing into the heavens at this marvelous demonstration of what we now know to be the birth of aviation, someone in the crowd (probably wearing a beret) asked what might have seemed like a reasonable question at the time, “What is it good for?”

In other words, what practical use is the ability to float a wicker basket full of wine guzzling aeronauts over Paris in a hot air balloon?

Point well taken. Fortunately, our favorite forefather was on-site, with his memorably infantile response.

Franklin compared what must have seemed like an entertaining outdoor parlor trick, to that of a newborn child. To Franklin, this young babe of a creation was still unformed and untested—yet, filled with immense potential and possibility.

“Besides, the baby was cute,” laughs Jon Winter, co-founder. “You don’t know where these little discoveries will lead, but they do, and sooner or later add up to something bigger, like when they discovered that electricity and magnetism were two sides of the same coin.”

Electromagnetism is a fundamental force that dominates our everyday life. Power generators, communication systems, electronics and computing would not exist without our understanding of this profound force in our natural world.

Yet, until recently, this wonderous and pervasive power was largely unknown.

Ever since the publication of De Magnete (1600)—William Gilbert’s treatise on the similarities between static electricity and the magnetic lodestone—natural philosophers all over Europe began conducting experiments in a search for a greater link between these two newly discovered complimentary forces.

Little progress was made, until 1800 when Alessandro Volta (1745-1827), invented what Museum co-founder, President & CEO, John Jenkins calls the greatest electrical invention ever: the battery.

Volta’s batteries allowed English contemporary, Humphry Davy (1778-1829), to experiment by running continuous electricity through a platinum wire. Davy observed that the wire heated-up, and even glowed, due to the wire’s resistance to the increased current—establishing the connection between electricity, heat, and light.

Sir Davy was unaware that by running current through a wire he was creating more than heat he could feel, or light he could see—but something else, something invisible and profound.

Something right under his nose.

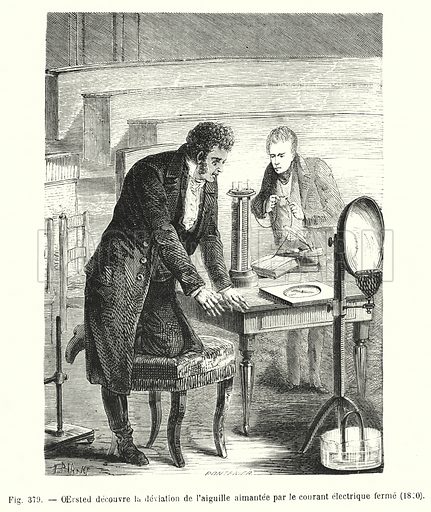

Almost twenty years later, Danish physicist Hans Christian Oersted, (1777-1851) also conducted detailed experiments on the relationship between electricity, heat, and light. Yet, Oersted took his concept a step further. He had an idea electricity and magnetism were also connected, and decided to test his theory using, among other things, a compass.

After months of intensive investigation, Oersted discovered that by placing a compass under a platinum wire connected to a battery, and switching the current off and on, he could make the needle jump, showing that an electric current produces a magnetic field as it flows through a wire. He also discovered the magnetic field around the wire was circular, and the lines of force were centered on the wire.

Oersted had discovered electromagnetism. Nice looking kid. Wonder how they’ll turn out…

On July 21, 1820, Oersted published ‘Experiments on the Effect of an Electrical Current on the Magnetic Needle’, thereby jolting the scientific community into a dynamic new branch of physics, and launching the Age of Electromagnetism.

Some of the greatest experimenters and engineers in the history of science—including Michael Faraday, André-Marie Ampère, James Clerk Maxwell, and William Sturgeon—were profoundly influenced by Oersted’s discoveries, and made monumental contributions toward making today’s modern world a reality.

Oersted wasn’t looking to power the world with electric motors and generators, or create a mass communication system. He wasn’t looking to electrify humanity by unlocking one of nature’s most profound secrets. As far as we know, he never wanted to go to the moon—but we did go to the moon, because his one small step led to another, and another.

That’s science for you: One day you’re playing around with some metal wire, an old compass, and a little battery, and the next you’re swinging a golf club on the surface of the moon.

Stay grounded.